Animal Digestive Systems

From new treatments for gastrointestinal diseases and disorders to the complicated ways that our gut microbiota can affect many aspects of our health, we tend to focus on what goes on in our own digestive tracts quite frequently. However, if we switch the focus away from humans, and glimpse into the animal kingdom, we will find a vast diversity of digestive systems among various animals, which is a testament to the complexity and importance of digestion to life on Earth, and helps us understand why the dietary requirements between humans and other animals can be quite different.

Snakes

For pythons, native to India and Myanmar, digesting a meal is serious business that requires drastic anatomical changes. In fact, as a python begins digestion its heart mass increases by 40%, its pancreas enlarges by 94%, and its liver more than doubles in size!1

For pythons, native to India and Myanmar, digesting a meal is serious business that requires drastic anatomical changes. In fact, as a python begins digestion its heart mass increases by 40%, its pancreas enlarges by 94%, and its liver more than doubles in size!1

The ability to open the mouth several times the width of the head as it swallows food is unique to snakes. They can separate and move the sides of their jaws independently in order to ‘walk’ the mouth around large prey. Unlike humans, the snake’s tongue has no role in the swallowing process. Instead, salivary glands moisten the mouth to lubricate the prey as it travels into the esophagus. The tongue exists to help the snake locate prey by detecting smells (chemoreception), so a snake without a tongue might have difficulty finding food.2

The human esophagus is a muscular tube that moves food from the mouth to the stomach through a series of wave-like muscle contractions known as peristalsis. A snake’s esophagus, however, has very little muscle. It relies on the muscles of the entire body to squeeze food through the esophagus into the stomach. From there, digestion takes anywhere from three days to a few weeks to complete.3 The duration depends on the size of the snake and the size of its meal. Larger snakes, such as pythons, eat larger prey and, therefore, need more time for digestion.

The stomach of a snake is short and narrow, with a muscular wall and interior folds that increase the surface area for digestion and absorption. In comparison to a human’s intestine, a snake’s small intestine and large intestine are not differentiated. The small intestine is generally narrower than the large intestine and both are able to expand and shrink due to the normal intermittent feeding behaviour of snakes. The colon then carries the fecal matter to the coprodeum and then to the proctodeum where it mixes with urinary excreta and is stored before moving to the cloacal opening for disposal. Similar to birds, the cloaca is a common chamber that products from the digestive, urinary, and reproductive systems pass through.

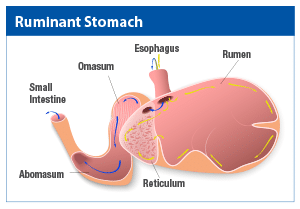

Cows

When a cow grazes, it rips up sections of plant material (grass, in most cases), chews only a few times to mix the food with saliva, and then swallows the mixture (bolus).

When a cow grazes, it rips up sections of plant material (grass, in most cases), chews only a few times to mix the food with saliva, and then swallows the mixture (bolus).

However, unlike in humans, acidic digestion in the stomach does not begin right away. As a ruminant animal, along with sheep, goats, and deer, a cow’s lower esophagus has three chambers – the rumen, reticulum, and omasum – and the stomach is called an abomasum. Initially, the rumen stores food during grazing, holding up to 50 gallons of undigested material.4 After grazing, the cow returns food to the mouth from the rumen via the esophagus for more chewing and the addition of saliva.

In the rumen, bacteria and other microorganisms break down the plant cellulose into simple sugars and short-chain fatty acids. In a symbiotic relationship, the bacteria break down the plant matter and the cow absorbs nutrients from both the bacteria and the broken down food, allowing the cow to receive energy from its food early in the digestion process.

The second pouch, the reticulum, acts as a trap for large objects leaving the rumen. Once the food material has been broken down enough in both the rumen and reticulum, it passes into the omasum. There, tiny projections on the surface of the omasum’s lining absorb water and minerals. The omasum pumps the food into the abomasum, where acid digestion, similar to that in humans, finally occurs.

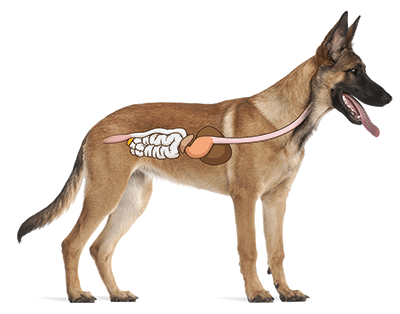

Dogs

Both humans and dogs have a one-stomach system for digestion (monogastric). However, a dog’s digestive system differs from that of a human in several ways. In humans, digestion begins in the mouth, where enzymes in saliva begin breaking down starches into simple sugars as we chew. However, a dog’s mouth takes care of biting and crushing, allowing the dog to swallow large pieces of meat, bone, and fat quickly without chewing,5 and making the dog’s stomach the primary starting point in its digestive process.

Both humans and dogs have a one-stomach system for digestion (monogastric). However, a dog’s digestive system differs from that of a human in several ways. In humans, digestion begins in the mouth, where enzymes in saliva begin breaking down starches into simple sugars as we chew. However, a dog’s mouth takes care of biting and crushing, allowing the dog to swallow large pieces of meat, bone, and fat quickly without chewing,5 and making the dog’s stomach the primary starting point in its digestive process.

A dog’s stomach contains hydrochloric acid, which begins to break down the large pieces of protein that it has ingested, while its muscular gastric folds help grind and digest its meal. Food passes into the first segment of the small intestine (duodenum) in liquid form, where the main part of digestion occurs and nutrients are absorbed. Consisting of three distinct parts – the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum – the small intestine operates similarly to those of humans.

A dog’s large intestine connects the small intestine to the anus. It is about 16 inches long in a 40-pound dog6 and works to absorb water from feces as needed, keeping the dog’s hydration levels constant. The final section of the large intestine is the rectum, which stores fecal matter awaiting elimination.

Like most carnivores, the dog has a short digestive system relative to its body size, and it takes about 8-9 hours for the entire digestive process.7 Dogs also have a regurgitation process, which allows them to spit up food that it has not processed correctly, such as plant matter.

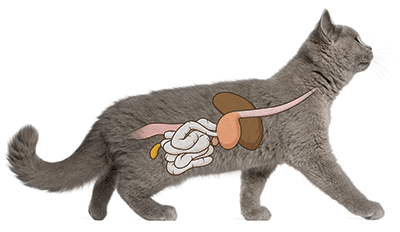

Cats

One myth about cats is that they eat grass only when they are sick. Actually, cats eat grass to aid in digestion and to help them get rid of any fur or undigested material in their stomachs after self-grooming or consuming mice and birds.8 When a cat is at rest, the walls of its esophagus collapse in on each other to form a closed space. As in humans, muscles in its esophagus contract to push food into the stomach. The inner stomach lining releases acids and enzymes, which break down the food. Most food leaves the stomach twelve hours after entering.9

One myth about cats is that they eat grass only when they are sick. Actually, cats eat grass to aid in digestion and to help them get rid of any fur or undigested material in their stomachs after self-grooming or consuming mice and birds.8 When a cat is at rest, the walls of its esophagus collapse in on each other to form a closed space. As in humans, muscles in its esophagus contract to push food into the stomach. The inner stomach lining releases acids and enzymes, which break down the food. Most food leaves the stomach twelve hours after entering.9

Similar to humans and dogs, a cat’s small intestine has three parts – the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum – and the gallbladder and pancreas connect to the duodenum via bile and pancreatic ducts. Additional products created in the liver pass through these ducts and mix with the food in the duodenum. The jejunum is the longest area of the small intestine and has many small finger-like projections (villi), which absorb nutrients. The remaining contents pass via the ileum into the large intestine.

The large intestine absorbs water from feces as needed, helping to keep the cat’s hydration levels consistent. The large intestine has three parts, the cecum, colon, and rectum. In cats, the cecum is a small, finger-like projection near the junction with the small intestine. It appears to be mostly rudimentary in the large intestine of most carnivores. The colon is the longest portion and ends with the rectum where fecal matter is stored for passage from the body. In total, digestion in a cat’s body takes roughly 20 hours.10

Birds

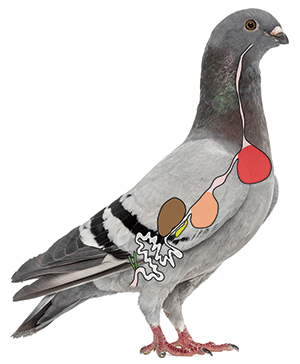

The beak, which is a thick, keratinized structure, grows continually through a bird’s life and wears off as it is used. The bird’s esophagus is a wide diameter tube that moves food along through peristalsis, just as in human digestion. However, in place of a stomach, birds have a food storage compartment (crop).11 From a reproductive perspective, the crop plays a critical role in childrearing for birds. Crops allow both male and female birds to bring home food to regurgitate to their younglings.

The beak, which is a thick, keratinized structure, grows continually through a bird’s life and wears off as it is used. The bird’s esophagus is a wide diameter tube that moves food along through peristalsis, just as in human digestion. However, in place of a stomach, birds have a food storage compartment (crop).11 From a reproductive perspective, the crop plays a critical role in childrearing for birds. Crops allow both male and female birds to bring home food to regurgitate to their younglings.

Birds have two stomachs, the proventriculus and ventriculus. The proventriculus is similar in function to the monogastric stomach. It is smooth and muscular with a protective lining, and is where protein begins to break down. The ventriculus, more commonly known as the gizzard, is the muscular stomach that uses stones or grit to grind food into smaller particles. Since birds have no teeth for chewing, the muscular contractions of the ventriculus force the food material between the stones. When consistency is appropriate, the food returns to the proventriculus for further digestion.

Although the bird’s small intestine is not significantly different from that of mammals, its large intestine begins with caeca, which are two pouches that function to absorb some of the water remaining in the products of digestion. Caeca vary greatly in size, but they provide a site for cellulose to break down and for the formation of fatty acids, which contribute to a bird’s energy supply. Birds have a short colon and, unlike mammals, they have only one opening for the digestive, urinary, and reproductive tracts, known as the cloaca or vent.

Conclusion

The digestive systems of animals are incredibly complex and diverse. While some components may act similarly to those of humans, the truth is that each system is unique to its species and determines what the animal eats, how often it eats, and sometimes how it raises its young.

Reviewed by Toronto Zoo

Toronto Zoo is accredited by Canada’s Accredited Zoos and Aquariums (CAZA) and Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA). Look for these logos whenever you visit a zoo as your assurance that you are supporting a facility dedicated to providing excellent care for animals, a great experience for you, and a better future for all living things. With its more than 200 accredited members, AZA is a leader in global wildlife conservation, and your link to helping animals in their native habitats. For more information, visit www.caza.ca or www.aza.org

First published in the Inside Tract® newsletter issue 201 – 217

Images: © TANGOART | Bigstockphoto.com, © Life on White | Bigstockphoto.com, © Alexsnail | Bigstockphoto.com

1. Secor SM. Digestive physiology of the Burmese python: broad regulation of integrated performance. Journal of Experimental Biology. 2008;211:3767-3774.

2. Avila LA et al. Garter snakes do not respond to TTX via chemoreception. Chemoecology. 2012;22(4):263-258.

3. Snakes: Facts. Science Trek. Available at: http://idahoptv.org/sciencetrek/topics/snakes/facts.cfm. Accessed 2016-07-26.

4. Animal structure and function. The University of Waikato. Available at: http://sci.waikato.ac.nz/farm/content/animalstructure.html. Accessed 2016-06-24.

5. How the dog digestive system works. VetInfo. Available at: https://www.vetinfo.com/dog-digestive-system.html. Accessed 2016-06-27.

6. Anatomy & function of the esophagus, stomach & intestines in dogs. Pet Education. Available at: http://www.peteducation.com/article.cfm?c=2+2090&aid=512. Accessed 2016-06-27.

7. How the dog digestive system works. VetInfo. Available at: https://www.vetinfo.com/dog-digestive-system.html. Accessed 2016-06-27.

8. Why do cats eat grass? Know Your Cat. Available at: http://www.knowyourcat.info/info/catingrass.htm. Accessed 2016-07-26.

9. Anatomy and function of the esophagus, stomach and intestines in cats. Pet Education. Available at: http://www.peteducation.com/article.cfm?c=1+2231&aid=511. Accessed 2016-07-27.

10. The Cat Encyclopedia. Penguin, 2014.

11. Avian digestive system. University of Kentucky College of Agriculture, Food and Environment. Available at: http://www2.ca.uky.edu/agcomm/pubs/asc/asc203/asc203.pdf. Accessed 2016-06-27.