Short-sighted policies, clickbait savings, and long-term damage to IBD patients

December 18, 2019

Gail Attara

President & Chief Executive Officer, Gastrointestinal Society

President, Canadian Society of Intestinal Research

Alberta’s policy decision to switch the treatments of thousands of patients to biosimilars comes under the guise of presumed cost-savings and at the behest of a few sacrifices from patients.

The non-medical switch policy, announced on December 12, 2019 affects an estimated 26,000 patients with certain types of arthritis, diabetes (Type 1 and 2), inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis), neutropenia, and multiple sclerosis. Government-sponsored drug plan coverage for originator biologics, which includes Remicade®, will be discontinued as of July 1, 2020, leaving those affected with just six months to see their specialist and healthcare team to switch to a biosimilar and enroll in a new patient support program, if necessary. The policy does not yet affect those with private drug plans, but I think it might soon.1

According to the government’s Biosimilars Initiative website, “A biosimilar drug is a highly similar version of the original biologic medication, known as an originator drug, but less expensive”.2 Health Minister, Tyler Shandro, flaunts the necessity of this policy, claiming that it will save $380 million dollars over the next four years. Yet Janssen Inc., manufacturers of Remicade® infliximab biologic, released a statement shortly after explicitly stating that they have offered proposals to the government to match the lower price of biosimilars.3

So, what is the government’s motive?

We have repeated time and again that biologics and biosimilars can never be exactly the same, due to their nature as composing of large and complex living cells created in strictly-controlled manufacturing and environmental conditions. While we, along with others in opposition of the policy, do not challenge the safety and efficacy of biosimilars, we do need to reiterate the importance of maintaining the health of patients stable on a biologic. This is particularly important in the IBD space (primarily Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis), where many patients have tried and failed various medications before Remicade®.

For these individuals, finding treatment (and its appropriate dosage) that finally works is a godsend. So much so that it has kept their lives as normal as possible and enabled them to go to work, free of the severe hardships that plagued them from the disease. With a looming transition, patients are feeling anxious and overwhelmed.

Yet while the government has assured patients that those wishing to stay on the biologic can apply for exceptional coverage, its comparative success in BC shows little promise. According to Calgary gastroenterologist Dr. Remo Pannacione’s sources, only 1 in 400 have been approved for exemptions in the province,4 meaning that only 55 patients out of the estimated 22,100 (0.24%) patients affected were approved access to stay on their medication.

According to a paper in press at the Journal of the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology, the best-case scenario for Alberta’s non-medical switch policy could result in more than 60 avoidable surgeries for every 2,000 IBD patients and, in the worst-case scenario, the number jumps to 184.5 Patients who experience adverse reactions to a switch, including some who may be admitted to the ER, be hospitalized, and/or go under surgical procedures as a result, are mere collateral damage as governments cherry-pick policy decisions in the face of evidence-based opposition from doctors and patient communities.

Is this what we aspire for healthcare to be like in Canada?

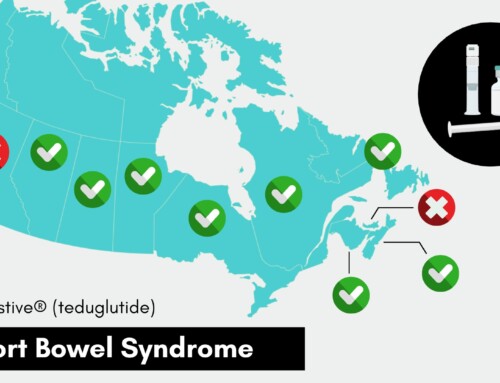

Among concerns that have already been voiced, including the lack of adequate consultation with IBD patients and specialists leading up to the government’s decision, we also need to ensure that this forced switching will be safe and appropriate. A number of biosimilars are delivered intravenously in-patient support programs. However, some infusion clinics have exclusivity contracts with pharmaceutical companies who either provide the biologic or biosimilar products. As we’ve learned from patients in BC, clinics that provide a biosimilar have limited capacity and availability, including hours of operation, geographic location, and staffing. Switching to a new clinic also means a new healthcare team for patients. There are dire consequences if clinics can’t keep up and patients are at risk for missing their next scheduled infusion. To date, there are 47 support programs in Alberta with 24 having exclusivity contracts with Janssen Inc. (original), 22 with Pfizer (biosimilar), and 12 with Merck (biosimilar).4,6

The increased awareness in Alberta presents an opportunity of sober reflection for decisionmakers and, crucially, a wiser biosimilar approach moving forward. The UCP Alberta government policy followed in the heels of BC, led by an NDP government and, frankly, one of the rare few among healthcare systems in the world to force a non-medical switch on patients.7 Other provinces are looking to adopt biosimilar switch policies in early 2020. We hope that they listen to our concerns.

Saskatchewan, the birthplace of Canadian healthcare, and PEI have it right. Why are the other jurisdictions so far off the mark? Stay tuned.