The Unassuming Wonders of the Esophagus

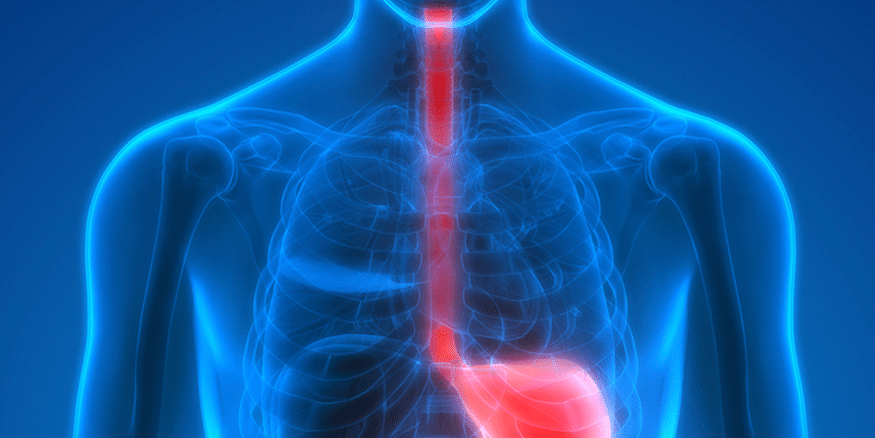

Located behind the mighty lungs and heart, the esophagus works hard for us but its function is something many of us take for granted. It seems simple enough – you swallow, food and liquids go down your throat and, shortly after, land in your stomach. End of story.

In fact, the actions of the esophagus are so complex that scientists still do not understand them fully. As they discover the intricacies of the many processes involved in a simple swallow, researchers become better equipped to study the conditions that arise when even just one part of the esophageal system malfunctions.

Peristalsis is the normal downward pumping and squeezing of the esophagus, stomach, and small intestine. When you swallow, the longitudinal muscle layers of the esophagus contract to increase muscle wall thickness at the very site and time that circular muscles contract to increase pressure.1 These muscles normally move in perfect synchronicity in a downward wave pattern, pushing food contents down the esophagus and into the stomach in about nine seconds.2

Two important components of the esophagus are the upper esophageal sphincter (UES) and the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), and the actions of each of these sphincters are involuntary and under control of the brainstem. Swallowing triggers the opening of the UES to push food into the esophagus. The LES, which is located at the bottom of the esophagus where it meets the stomach, normally stays fully closed, but it relaxes and opens briefly when food reaches it, to allow it to pass into the stomach.

Heartburn occurs when the LES malfunctions by not closing quickly enough or remaining slightly open, allowing the acidic contents of the stomach to move back up into the esophagus. In untreated gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), this backflow recurs regularly.

Achalasia is an uncommon disorder in which there is a lack of peristalsis and/or failure of the coordinated relaxation of the LES during swallowing, preventing esophageal contents from entering the stomach. Typically, the muscles of the LES relax when it receives specific messages from the brain, but researchers have found that the LES actually opens through a different mechanism that they don’t yet fully understand.3 In achalasia, there is degeneration of the nerve cells that signal the brain to relax the LES. Interestingly, in 10% of achalasia patients, the LES relaxes normally but still does not open.

There is much more involved in swallowing than mere muscle movement. The stimulus-response function of the esophagus also involves a complicated system of sensory pathways that run to and from the brain. Different sensory neurons (nocireceptors) inside the esophageal wall sense thermal, chemical, and mechanical stimuli, which help to trigger the involuntary actions of the esophageal muscles. Those with non-erosive reflux disease (NERD) and functional dyspepsia (a chronic disorder affecting the sensation of peristalsis) tend to be hypersensitive to these stimuli.

About 25% of the sensory fibres connecting the esophagus to the brain pass nearby neurons that also receive sensory information from the heart. This is why it is sometimes difficult to distinguish pain related to a problem with the heart (e.g., angina) from esophageal pain. Interestingly, anxiety, depression, and stress also affect the neural pathways from the esophagus, which can result in amplified esophageal pain without a corresponding physical stimulant.

We have really only touched on the basics of how the esophagus works and the conditions that can result if some part of the esophageal system malfunctions. It may not have the celebrity of the lungs or heart, or even the more prominent areas of the digestive tract such as the stomach or fascinating intestines, but the esophagus is a mighty organ in its own right. Like a shy, smart, friend, it coordinates with the brain and other areas of the body to make those necessary swallows as easy and uneventful – and usually unnoticed – as they can be.

Esophageal Cancers

Cancers of the esophagus are rare, but incidences continue to increase worldwide and the mortality rate for those with these diseases is very high. The chance of living for at least 5 years after diagnosis is only 14%.4 Researchers urge individuals to become aware of and avoid the risk factors for esophageal cancers, because by the time symptoms such as chest pain, fatigue, weight loss, and progressive difficulty swallowing appear, the tumour has likely already progressed to a later stage, making treatment difficult. If you are experiencing any of the symptoms listed above or a significant change in your GERD symptoms, make an appointment to talk it over with your physician.

Six Tips to Reduce Your Risk*

- Don’t smoke

- Eat lots of fruits and vegetables

- Avoid hot beverages

- Limit alcohol

- Keep a healthy weight

- Manage your GERD

*Adapted from a Johns Hopkins Health Alert5