Click here to download a PDF of this information.

Ulcerative Colitis

Ulcerative colitis is unrelated to ulcers found elsewhere in the gastrointestinal tract, such as stomach or duodenal ulcers, but it has many similarities to Crohn’s disease, another IBD. The main differences between Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are that, in Crohn’s disease, the inflammation extends into the bowel muscle wall and can affect any part of the digestive tract, whereas in ulcerative colitis, disease is limited to the surface lining of the colon.

The cause of ulcerative colitis is undetermined but there is considerable research evidence to suggest that interactions between environmental factors, intestinal bacteria, immune dysregulation, and genetic predisposition are responsible. There is an increased risk for those who have a family member with the condition. Although there is a range of treatments to help ease symptoms and induce remission, there is no cure.

A diagnosis of ulcerative colitis can occur at any point throughout life, with a high occurrence in young children and for those who are between 40-50 years of age. Currently, Canada has among the highest prevalence and incidence yet reported in the world, with approximately 143,000 diagnosed individuals.

Ulcerative Colitis Symptoms

Rectal bleeding is common and can occur in varying amounts. The blood is usually obvious within and on the surface of the stool. The second most frequent symptom is diarrhea, accompanied by cramping and abdominal pain. Symptom intensity can range from mild to severe. Low red blood cell count (anemia) can result if diarrhea and blood loss are severe. Constipation can also develop as the body struggles to maintain normal bowel function.

Since ulcerative colitis is a systemic disease, it can affect other parts of the body, so some individuals will have extra-intestinal manifestations, including fever, inflammation of the eyes or joints, ulcers of the mouth, or tender, inflamed nodules on the shins.

If you have had ulcerative colitis for about 10-15 years, you are at a slightly increased risk for colorectal cancer, so your physician might recommend screening for this sooner than typical for of the general population.

Diagnosing Ulcerative Colitis

Your physician will carefully review your medical history. Blood tests are useful in assessing inflammation activity level, whether blood loss has resulted in anemia, and your overall health and nutritional state. Stool sample analysis can sometimes be helpful.

It takes time to obtain a diagnosis, so it is a good idea to keep a journal or diary about symptoms, when they appear, and how you feel. As you discuss these symptoms with your physician, they will be in a better position to form a diagnosis for you.

Your physician will determine which of several procedures is best to assess your intestinal symptoms. Although not used often anymore, X-rays allow your physician to view the contours of your bowel. The procedure requires you to undergo a barium enema. This provides contrast that helps the intestine show up on X-ray. More often now, scopes help to determine the nature and extent of the disease. In these procedures, the physician inserts an instrument into the body via the anus (sigmoidoscope/colonoscope) to allow for visualization of the colon. The scopes are made of a hollow, flexible tube with a tiny light and video camera. An advantage of these procedures over a barium X-ray or virtual colonoscopy (CT scan) is that a physician may biopsy suspicious-looking tissue at any time during the examination for subsequent laboratory analysis.

Once all of this testing is complete, and other possible conditions are ruled out, your physician may make a diagnosis of ulcerative colitis.

Management of Ulcerative Colitis

The treatment of ulcerative colitis is multi-faceted; it includes managing the symptoms and consequences of the disease along with therapies targeted to reduce the underlying inflammation. The goal is to heal the lining of the colon (mucosal healing) and to stay in remission.

Dietary and Lifestyle Modifications

As most nutrients are absorbed higher up in the digestive tract, those with ulcerative colitis generally do not have nutrient deficiencies; however, other factors might influence your nutritional state. Disease symptoms may cause food avoidance, leading to food choices that might not provide a balanced diet. If bleeding is excessive, problems such as anemia may occur, and modifications to the diet will be necessary to compensate for this.

Generally, better overall nutrition provides the body with the means to heal itself, but research and clinical experience show that diet changes alone cannot manage this disease. Depending on the extent and location of inflammation, you may have to follow a special diet, including supplementation. It is important to follow Canada’s Food Guide, but this is not always easy for individuals with ulcerative colitis. We encourage you to consult a registered dietitian, who can help set up an effective, personalized nutrition plan by addressing disease-specific deficiencies and your sensitive digestive tract. Some foods may irritate the bowel and increase symptoms even though they do not worsen the disease.

In more severe cases, it might be necessary to allow the bowel time to rest and heal. Specialized diets, easy to digest meal substitutes (elemental formulations), and fasting with intravenous feeding (total parenteral nutrition) can achieve incremental degrees of bowel rest.

Symptomatic Medication Therapy

The symptoms are the most distressing components of ulcerative colitis, and direct treatment of these symptoms, particularly pain and diarrhea, will improve quality of life. Several treatments exist to address diarrhea and pain. Dietary adjustment may be beneficial and anti-diarrheal medications have a major role to play. Analgesics can be helpful for managing pain not controlled by drugs that address the underlying inflammation, listed below. Acetaminophen (Tylenol®) is preferred over medications called non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen (Advil®, Motrin®), aspirin, and naproxen (Aleve®, Naprosyn®), as they can irritate the gut.

There are two types of anti-diarrheal medications directed at preventing cramps and controlling defecation. One group alters the muscle activity of the intestine, slowing down content transit. These include: non-narcotic loperamide (Imodium®); narcotic agents diphenoxylate (Lomotil®), codeine, opium tincture and paregoric (camphor/opium); and anti-spasmodic agents dicyclomine HCL and hyoscine butylbromide (Buscopan®).

The other group adjusts stool looseness and frequency by soaking up (binding to) water, regulating stool consistency so it is of a form that is easy to pass. Plant-based products are helpful such as inulin fibre (Benefibre®) and psyllium (ispaghula) husk (Metamucil®). Plant fibres are also useful to manage constipation, due to their stool regulating effects. Cholestyramine resin, a bile salt binder, can also help with stool looseness.

If extra-intestinal signs of ulcerative colitis occur, such as arthritis or inflamed eyes, your physician will address these conditions individually, as you might require referrals to other specialists. If anxiety and stress are major factors, a program of stress management may be valuable.

Individuals with ulcerative colitis may be anemic from chronic blood loss. Iron supplements could help improve this condition, with oral heme iron polypeptide (e.g., Hemaforte 1, Hemeboost, OptiFer® Alpha, Proferrin®) being the preferred option, due to quick-acting and low side-effect profiles. Iron isomaltoside 1000 (Monoferric™), iron sucrose (Venofer®), and sodium ferric gluconate (Ferrlecit®) are indicated for intravenous (IV) treatment of iron deficiency anemia in adults who have intolerance or unresponsiveness to oral iron therapy. Occasionally, a blood transfusion may be necessary.

The most widely prescribed antibiotics are ciprofloxacin (Cipro®) and metronidazole (Flagyl®). Broad-spectrum antibiotics are important in treating secondary manifestations of the disease, such as peri-anal abscess and fistulae.

Anti-inflammatory Therapy

These come in many forms, using various body systems. A physician may prescribe any of the following medications alone or in combination. It could take some time to find the right mix for an individual, as each case of ulcerative colitis is unique. Depending on the location of your disease, the combination of drug delivery method (oral and rectal) could help to ensure that all areas of the disease are covered.

5-Aminosalicylic Acid (5-ASA)

5-ASA medication is safe and well tolerated for long-term use in mild cases of ulcerative colitis. These medications, taken orally, include mesalamine (Mezavant®, Mezera®, Octasa®, Pentasa®, Salofalk®) and olsalazine sodium (Dipentum®). Quicker results might occur when medication is used in a topical form, taken rectally. Salofalk® is available in 500 mg and 1 g suppositories. Salofalk® 1 g and Pentasa® 1 g suppositories are once-a-day therapies. Mezera® is available in a 1 g suppository or a 1 g foam enema. In a more difficult case, you may receive 5-ASA enema therapy (Salofalk® 4 g & 2 g/60 mL and Pentasa® 1 g, 2 g, or 4 g/100 mL) for a short course, followed by suppositories, as the inflammation improves. Octasa® is available as an oral tablet, taken once daily. Some individuals may benefit from a combination of orally and rectally administered 5-ASA therapies in cases that do not respond to rectal therapy alone. A combination of 5-ASA and sulfa antibiotic is available orally as sulfasalazine (Salazopyrin®). Patients use rectal medications nightly at first and, as the disease improves, treatments become less frequent. Sometimes your doctor will stop treatment and start it again if there is a flare up, and sometimes maintenance therapy two to three times a week may be required long-term. Typically, your physician will start you on one type of preparation and, if there is inadequate response, will switch you to another type.

5-ASA helps to settle acute inflammation and, when taken on a long-term basis (maintenance), it tends to keep the inflammation inactive. It is important to keep up your medicine regimen even if your symptoms disappear and you feel well again. Maintenance therapy can be at the full initial dosage or at a reduced dosage and interval, depending on the disease response.

Corticosteroids

To reduce inflammation for the short-term in ulcerative colitis, corticosteroids can help. Oral medications include prednisone for mild to severe ulcerative colitis and budesonide (Cortiment®) for mild to moderate ulcerative colitis, although prednisone tends to have greater side effects. These medications can be helpful to induce remission but should not be used long-term or for maintenance.

Oral budesonide (Cortiment®) is designed to provide topical release of the medication directly in the colon, whereas hydrocortisone and betamethasone are available for rectal administration (enemas, foams, and suppositories). However, if you have significant diarrhea, then these medications may be difficult to hold inside the rectum. A new rectal foam, budesonide (Uceris®), and an oral medication for hydrocortisone (Auro-Hydrocortisone), are also available.

In more complex cases, physicians may prescribe hydrocortisone (Solu-Cortef®) and methylprednisolone (Solu-Medrol®) for administration intravenously in-hospital.

Oral vs. Rectal Treatments

Most physicians prescribe ulcerative colitis patients oral versions of 5-ASAs or corticosteroids, since this is a patient-preferred delivery method of medication. However, even if they have a specially designed release mechanism, they might not reach and treat the area where the disease is most active.

For example, when you apply sunscreen to your skin, you need to make sure that you cover every exposed part to protect it from the sun. Similarly, when applying these treatments to your rectum and lower colon, you need to make sure that the product covers all of the inflamed areas.

Oral tablets might not be the optimal way to reach the end of the colon, where stool and the fact that ulcerative colitis patients have diarrhea, might interfere with its effectiveness. Unfortunately, this is also the area in the colon where a flare usually starts. The best way to reach this particular area is by inserting the drug directly into the rectum.

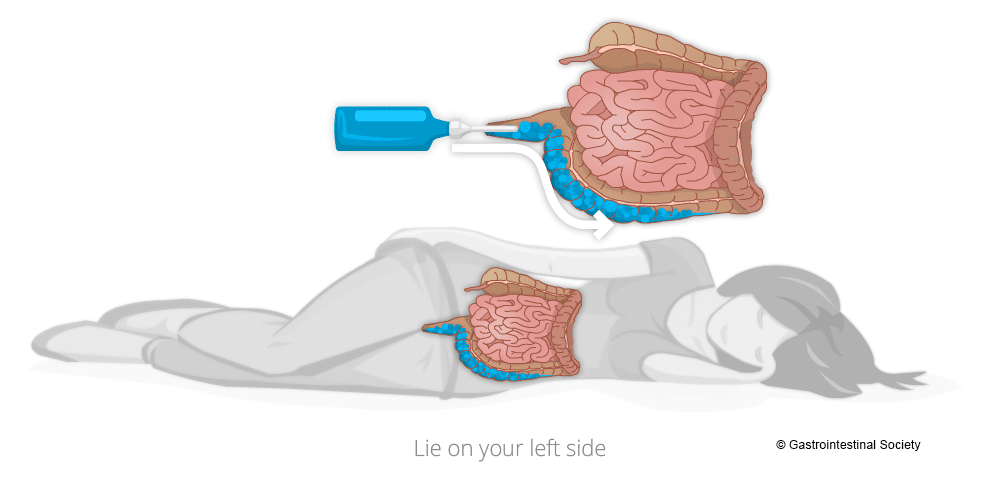

The medication released from a suppository will travel upward and usually reach about 15 cm inside from the anus. An enema (liquid form) will reach farther, about 60 cm. Those with ulcerative colitis usually insert these formulations before bedtime, and this way the medication is retained as long as possible. Stool does not usually interfere with the drug, as the rectum is typically relatively empty right before bed.

Rectal preparations are particularly good at treating urgency and bleeding, symptoms that often are very bothersome. A positive response often occurs within days of treatment.

Administering Rectal Therapies

To get the best coverage of topical rectal therapies, it is best to lie down on your left side. As you will see from the accompanying diagrams, the human anatomy is not symmetrical and the way the organs lay when on the left side makes for better medication administration. Talk with your pharmacist for more information to help with proper use and administration of rectal therapies.

Immunosuppressive Agents

Small Molecules

These drugs are used to treat ulcerative colitis, to reduce dependence on steroids, and for those who have steroid-resistant disease. They include azathioprine (Imuran®), cyclosporine, mercaptopurine/6-MP (Purinethol®), and methotrexate sodium (Metoject®). These medications can take up to twelve weeks of therapy to start working and six months to be fully effective.

There are newer classes of medications that target inflammation. These are Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors and sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) inhibitors.

JAK inhibitors typically work faster than biologics, pose no risk for immunogenicity, and are easy and convenient to take since they are in pill form. These include a pan-JAK-inhibitor (Xeljanz®) and a selective-JAK-inhibitor upadacitinib (Rinvoq®).

S1P inhibitors are immunomodulators and act as a receptor agonist, sequestering lymphocytes to peripheral lymphoid organs and away from their sites of chronic inflammation. Currently, there are two drugs in this class, ozanimod (Zeposia®) and etrasimod (Velsipity™).

Biologics (Large Molecules)

Biologic medications are important treatment options for those who have moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. Biologics are specially developed proteins, which selectively block molecules that are involved in the inflammatory process. Gastroenterologists routinely prescribe biologics to reduce inflammation and control the symptoms (induce clinical remission) of ulcerative colitis.

The first biologic that Health Canada approved to treat ulcerative colitis was the anti-TNF agent infliximab (Remicade®) in 2006. Later biologics include anti-TNF agents, adalimumab (Humira®) and golimumab (Simponi®), an alpha-4/beta-7 integrin inhibitor, vedolizumab (Entyvio®), an IL-12/23 inhibitor, ustekinumab (Stelara®), and an IL-23 inhibitor, mirikizumab (Omvoh™). As the patents expire for these medications, biosimilars come to market. So far, there are biosimilars of infliximab (Avsola®, Inflectra®, Ixifi®, Omvyence™, Remsima™SC, Renflexis®), adalimumab (Abrilada®, Amgevita®, Hadlima®, Hadlima® PushTouch®, Hulio®, Hyrimoz®, Idacio®, Simlandi™, Yuflyma™), and ustekinumab (Wezlana™). See our website for more information about biosimilars.

These medications are proteins, which our bodies might identify as foreign invaders and then develop antibodies to fight them off, which can diminish the drug’s effectiveness over time. If you stop taking the drug for some time and then try to resume it, what worked wonderfully for you before might not work the next time you take it because of these antibodies. This means that it is extremely important that you only stop treatment if your physician advises you to do so. Stopping a treatment because you are feeling well might result in that drug not working to make you feel well again.

Currently, Humira® (and its biosimilars), Simponi®, Entyvio®, Stelara® (and its biosimilar), Skyrizi®, and Omvoh™ are available for self-administration under the skin (subcutaneous) and Remicade® (and its biosimilars, except Remsima™SC), Entyvio®, Stelara®IV, Wezlana™IV are available as intravenous (IV) infusion by a healthcare professional. The dosage of both types can be in various intervals, depending on the medication and the individual’s response. In some cases, you might need to start on a biologic medication by receiving it as an IV infusion and then move on to subcutaneous injection for maintenance.

One tool to help physicians be sure that patients are on the right medication at the right dose is Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM), which involves laboratory testing to determine the level of the drug in the system. A second vital test is fecal calprotectin, which measures an inflammatory substance in your stool. A gastroenterologist assesses these results in the context of a person’s symptoms at specific periods during the treatment schedule.

Surgery

In those with ongoing active disease that fails to respond to all forms of medical management, surgery may be necessary.

Since ulcerative colitis only involves the large bowel, removing this organ will remove the disease, but it is not a cure. Removing the colon can lead to other symptoms and complications. Although there are many variations to possible surgical procedures, a surgeon typically removes all or part of the colon (colectomy) and then brings the end of the remaining intestine through a new surgical opening in the abdominal wall (ostomy) to which the patient can attach a removable appliance to collect stool. An ostomy may be either temporary or permanent, depending upon the particular situation.

In recent years, new techniques have arisen whereby surgeons can preserve the anal muscle and create an internal pouch, or reservoir, from the remaining intestine, so that emptying pouch contents via the anus more closely resembles the normal anatomical route. However, with the loss of colon function, bowel movements have very high liquid content and move frequently. This means that even after surgery, patients could face troublesome gastrointestinal symptoms. One complication that can occur is pouchitis, which is inflammation within the surgically created pouch.

An emerging surgical therapy is intestinal transplantation, but there are barriers yet to overcome, such as tissue rejection and inflammation in the newly transplanted organ.

What is a Flare?

When you have ulcerative colitis, your physician will try to find the right medications to control your symptoms. However, since there is no cure, the systemic disease is always there. When the symptoms aren’t present, you are in remission. If the symptoms return, especially if they are worse than before, it is a flare. This is why it is important to continue taking any medications your doctor prescribes, even if you feel better. If you stop taking your medication, then you can increase your chance of experiencing a flare and progression of the disease. Infections, stress, and taking antibiotics or NSAIDs (including aspirin, ibuprofen, and naproxen) can also make you more susceptible to a flare.

When to Get Treatment

An increase in inflammation causes a flare, and the nature of inflammation means that you should treat it as quickly as you can. Inflammation grows exponentially, because inflammation itself causes an increase in inflammation. The longer you leave it untreated, the worse it will get. In addition, untreated inflammation not only leads to the symptoms associated with ulcerative colitis, it can also increase your risk of developing complications such as colorectal cancer down the line. Pay attention to your symptoms, and visit your physician if you notice that they change or increase even a small amount.

Flare Treatment Options

Particularly if you are seeing a gastroenterologist who has a long wait time to get an appointment, it is important to discuss with your physician in advance exactly what you should do if you experience a flare. For example, your physician might provide a prescription for a rectal preparation that you could purchase and use immediately, to avoid going untreated while waiting to get into the office. However, you should still call your physician’s office to report your symptoms. This is an important conversation to have with your healthcare team, so you can prepare for self-management, when necessary, while keeping them aware of your condition.

When you are having disease symptoms, the first step is usually to increase your current treatment. Ask your doctor to explain your options as to what you should do between visits:

- increase the dose of your oral medication (tablets)

- use a rectal formulation (suppository or enema)

- a combination of the above

Your specific situation and history will determine what your physician recommends. Ideally, you should have a plan in place outlining what you can do if you have a flare. If you have severe symptoms, you should seek immediate help, even if that means heading to the hospital emergency room.

Is it important to treat a flare early, or is it ok to wait a bit?

Inflammation typically does not resolve without treatment and early intervention has a better outcome than waiting to treat. At an early stage of a flare, a more optimal baseline (5-ASA) treatment is often enough to get the inflammation under control. If you wait, there is a greater risk that you might need drugs with greater side effects, such as oral steroids. By waiting, you will have to manage longer with your symptoms before getting relief. Living with constant or longer periods of inflammation might increase your risk for future complications, as inflammation might cause damage to the gut wall that accumulates in severity with each flare.

If you are experiencing worsening symptoms, you have probably already had the flare for some time without symptoms. Evidence shows that a stool test for inflammation in the colon, called fecal calprotectin, is often elevated for two to three months before any symptoms appear. Your colon might also start to show visual (during colonoscopy) evidence of inflammation before you have symptoms, or at least indicate an increased risk for a flare.

Looking into the colon gives a better, more reliable picture of what is truly going on with your disease. For this reason, your specialist might suggest a colonoscopy so they can have a closer look inside your colon to determine the best course of action. However, in most instances, a physician might still base a decision to prescribe medication on the severity and the nature of your symptoms. This is particularly the case when the symptoms are still mild.

Action Plans

Want to learn more about managing flares? We have printable Action Plans available for both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. These documents outline which symptoms are normal, which indicate a flare, and which require emergency care. They also contain spaces to write in details about your medications, disease status, and healthcare team contact information.

Ulcerative Colitis Outlook

Ulcerative colitis is a chronic, systemic inflammatory disease manifesting in the colon. Intensity of this condition varies greatly from person to person and during a lifetime. Some individuals may have an initial episode and then go into remission for a long period, some may have occasional flare-ups, and some others may have ongoing disease. Although there is no cure, ulcerative colitis patients require ongoing medical care, and must adhere to a proper nutrition and medication regimen, even when things appear to be going well.

Your physician will work with you to create an appropriate treatment plan, and will monitor your disease regularly, even during periods of remission. Medication related questions can be directed to your pharmacist, who can be a valuable resource for administering your medications.

Video: Living With UC

Want to learn more about ulcerative colitis?

We have several related articles that may be helpful:

- Ulcerative Colitis

- Ulcerative Colitis Patient Journey

- Ulcerative Colitis Infograph

- Ulcerative Colitis Lecture

- BadGut® Stories

- IBD and the Balanced Dinner Plate

- Living with IBD: Tips From Our Support Groups